1 Introduction

The advancement of science is built on our ability to study and assess research hypotheses. This chapter covers the basic concepts of experiments, starting with vocabulary associated with the field. Emphasis is placed on the difference between experiments and observations.

This course covers experimental designs. In an experiment, the researcher manipulates one or more features (say the complexity of a text the person must read, or the type of advertisement campaign displayed, etc.) to study their impact. In general, however (Cox 1958)

effects under investigation tend to be masked by fluctuations outside the experimenter’s control.

The purpose of experiments is to arrange data collection so as to be capable of disentangling the differences due to treatment from those due to the (often large) intrinsic variation of the measurements. We typically expect differences between treatments (and thus the effect) to be comparatively stable relative to the measurement variation.

- Learning the terminology associated to experiments.

- Assessing the generalizability of a study based on the consideration of the sample characteristics, sampling scheme and population.

- Distinguishing between observational and experimental studies.

- Understanding the rationale behind the requirements for good experimental studies.

1.1 Study type

There are two main categories of studies: observational and experimental. The main difference between the two is treatment assignment. In observational studies, a feature or potential cause is measured, but not assigned by the experimenter. By contrast, the treatment assignment mechanism is fully determined by the experimenter in the latter case.

For example, an economist studying the impact of interest rates on the price of housing can only look at historical records of sales. Similarly, surveys studying the labour market are also observational: people cannot influence the type of job performed by employees or their social benefits to see what could have happened. Observational studies can lead to detection of association, but only an experiment in which the researcher controls the allocation mechanism through randomization can lead to directly establish existence of a causal relationship. Because everything else is the same in a well controlled experiment, any treatment effect should be in principle caused by the experimental manipulation.1

Figure 1.1 summarizes the two preceding sections. Random allocation of measurement units to treatment and random samples from the population lead to ideal studies, but may be impossible due to ethical considerations.

1.2 Terminology

In its simplest form, an experimental design is a comparison of two or more treatments (experimental conditions):

- The subjects (or experimental units) in the different groups of treatment have similar characteristics and are treated exactly the same way in the experimentation except for the treatment they are receiving. Formally, an experimental unit is the smallest division such that any two units may receive different treatments.

- The measurement unit is the smallest level (time point, individual) at which measurement are recorded; sometimes called observational unit in other textbooks.

- Explanatories (independent variables) are variables that impact the response. They can be continuous (dose) or categorical variables; in the latter case, they are termed factors.

- The experimental treatments or conditions are manipulated and controlled by the researcher. Oftentimes, there is a control or baseline treatment relative to which we measure improvement (e.g., a placebo for drugs).

- After the different treatments have been administered to subjects participating in a study, the researcher measures one or more outcomes (also called responses or dependent variables) on each subject.

- Observed differences in the outcome variable between the experimental conditions (treatments) are called treatment effects.

Example 1.1 (Pedagogical experience) Suppose we want to study the effectiveness of different pedagogical approaches to learning. Evidence-based pedagogical researchs point out that active learning leads to higher retention of information. To corroborate this research hypothesis, we can design an experiment in which different sections of a course are assigned to different teaching methods. In this example, each student in a class group receives the same teaching assignment, so the experimental units are the sections and the measurement units are the individual students. The treatment is the teaching method (traditional teaching versus flipped classroom).

The marketing department of a company wants to know the value of its brand by determining how much more customers are willing to pay for their product relative to the cheaper generic product offered by the store. Economic theory suggests a substitution effect: while customers may prefer the brand product, they will switch to the generic version if the price tag is too high. To check this theory, one could design an experiment.

As a researcher, how would you conduct this study? Identify a specific product. For the latter, define

- an adequate response variable

- the experimental and measurement units

- potential blocking factors

The main reason experiments should be preferred to collection of observational data is that they allow us, if they are conducted properly, to draw causal conclusions about the phenomenon of interest. If we take a random sample from the population of interest, split it randomly and manipulate only certain aspects, then all differences between groups must be due to those changes.

As Hariton and Locascio (2018) put it:

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are the reference standard for studying causal relationships between interventions and outcomes as randomisation eliminates much of the bias inherent with other study designs

Sometimes, it is impossible or unethical to conduct an experiment. This seemingly precludes study many social phenomena, such as the effect on women and infantile mortality of strict bans on abortions. When changes in legislation occur (such as the Supreme court overturning Roe and Wade), this offers a window to compare neighbouring states.

Canadian economist David Card was co-awarded the 2021 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his work in experimental economics. One of his most cited paper is Card and Krueger (1994), a study that looked at the impact of an increase in minimum wage on employment figures. Card and Krueger (1994) used a planned increase of the minimum wage of $0.80 USD in New Jersey to make comparisons with neighbouring Eastern Pennsylvania counties by studying 410 fast food outlets. The authors found no evidence of a negative impact on employment of this hike.

A study from which we can study causal relationships is said to have internal validity. By design, good experiments should have this desirable property because the random allocation of treatment guarantees, if randomization is well performed, that the effect of interest is causal. There are many other aspects, not covered in the class, that can threaten internal validity.

External validity refers directly to generalizability of the conclusions of a study: Figure 1.1 shows that external validity is directly related to random sampling from the population

In between-subjects designs, subjects are randomly assigned to only one of the different experimental conditions. On the contrary, participants receive many or all of the experimental treatments in a within-subjects design, the order of assignment of the conditions typically being random.

While within-subject designs allow for a better use of available ressources (it is cheaper to have fewer participants perform multiple tasks), observations from within-design are correlated and more subject to missingness and learning effects, all of which require special statistical treatment.

1.3 Review of basic concepts

1.3.1 Variables

The choice of statistical model and test depends on the underlying type of the data collected. There are many choices: quantitative (discrete or continuous) if the variables are numeric, or qualitative (binary, nominal, ordinal) if they can be described using an adjective; I prefer the term categorical, which is more evocative. The choice of graphical representation for data is contingent on variable type. Specifically,

- a variable represents a characteristic of the population, for example the sex of an individual, the price of an item, etc.

- an observation is a set of measures (variables) collected under identical conditions for an individual or at a given time.

Most of the models we will deal with are so-called regression models, in which the mean of a quantitative variable is a function of other variables, termed explanatories. There are two types of numerical variables

- a discrete variable takes a countable number of values, prime examples being binary variables or count variables.

- a continuous variable can take (in theory) an infinite possible number of values, even when measurements are rounded or measured with a limited precision (time, width, mass). In many case, we could also consider discrete variables as continuous if they take enough values (e.g., money).

Categorical variables take only a finite of values. They are regrouped in two groups, nominal if there is no ordering between levels (sex, colour, country of origin) or ordinal if they are ordered (Likert scale, salary scale) and this ordering should be reflected in graphs or tables. We will bundle every categorical variable using arbitrary encoding for the levels: for modelling, these variables taking \(K\) possible values (or levels) must be transformed into a set of \(K-1\) binary variables \(T_1, \ldots, T_K\), each of which corresponds to the logical group \(k\) (yes = 1, no = 0), the omitted level corresponding to a baseline when all of the \(K-1\) indicators are zero. Failing to declare categorical variables in your software is a common mistake, especially when these are saved in the database using integers (1,2, \(\ldots\)) rather than as text (Monday, Tuesday, \(\ldots\)).

We can characterize the set of all potential values their measurements can take, together with their frequency, via a distribution. The latter can be represented graphically using an histogram or a density plot2 if the data are continuous, or a bar plot for discrete or categorical measurements.

Example 1.2 (Die toss) The distribution of outcomes of a die toss is discrete and takes values \(1, \ldots, 6\). Each outcome is equally likely with probability \(1/6\).

Example 1.3 (Normal distribution) Mathematical theory suggests that, under general conditions, the distribution of a sample average is approximately distributed according to a normal (aka Gaussian) distribution: this result is central to most of statistics. Normally distributed data are continuous; the distribution is characterized by a bell curve, light tails and it is symmetric around it’s mean. The shape of the facade of Hallgrímskirkja church in Reykjavik, shown in Figure 1.2, closely resembles the density a normal distribution, which lead Khoa Vu to call it ‘a normal church’ (chuckles).

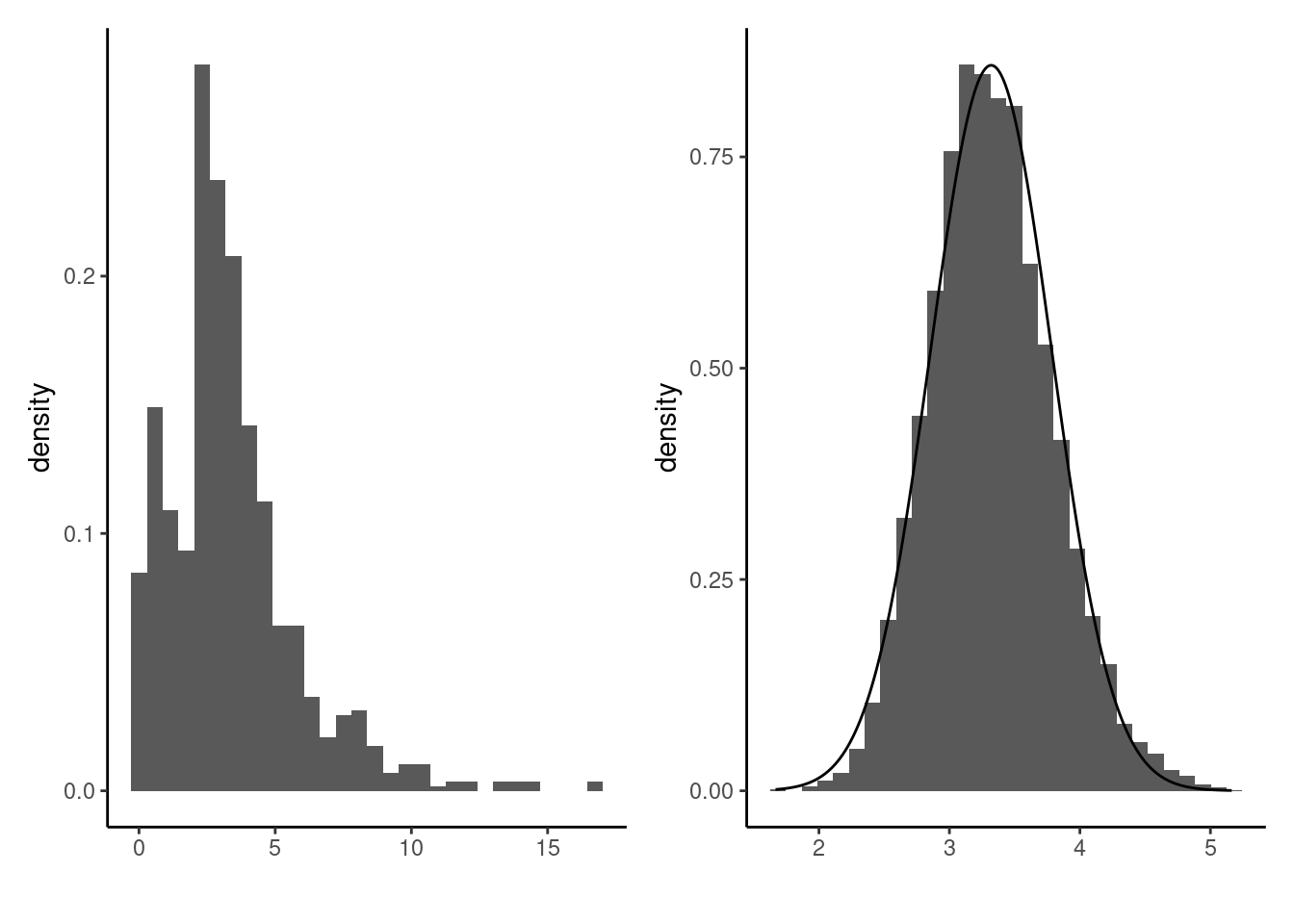

The normal distribution is fully characterized by two parameters: the average \(\mu\) and the standard deviation \(\sigma\). The left panel of Figure 1.3 shows an arbitrary continuous distribution and the values of a random sample of \(n=1000\) draws. The right panel shows the histogram of the sample mean value based on a very large number of random samples of size \(n=25\), drawn from the same distribution. The superimposed black curve is a normal density curve whose parameters match those given by the central limit theorem: the approximation is seemingly quite accurate.

This fact explains the omnipresence of the normal distribution in introductory data science courses, as well as the prevalence of sample mean and sample variance as key summary statistics.3

One key aspect, often neglected in studies, is the discussion of the metric used for measurement of the response. While previous research may have identified instruments (like questionnaires) and particular wording for studying a particular aspect of individuals, there is a lot of free room for researchers to choose from that may impact conclusions. For example, if one uses a Likert scale, what should be the range of the scale? Too coarse a choice may lead to limited capability to detect, but more truthfulness, while there may be larger intrinsic measurement with a finer scale.

Likewise, many continuous measures (say fMRI signal) can be discretized to provide a single numerical value. Choosing the average signal, range, etc. as outcome variable may lead to different conclusions.

Choosing a particular instrument or metric could be in principle done by studying (apriori) the distribution of the values for the chosen metric using a pilot study: this will give researchers some grasp of the variability of those measures.

At the heart of most analysis are measurements. The data presented in the course have been cleaned and oftentimes the choice of explanatory variables and experimental factor4 is evident from the context. In applications, however, this choice is not always trivial.

1.3.2 Population and samples

Only for well-designed sampling schemes does results generalize beyond the group observed. It is thus of paramount importance to define the objective and the population of interest should we want to make conclusions.

Generally, we will seek to estimate characteristics of a population using only a sample (a sub-group of the population of smaller size). The population of interest is a collection of individuals which the study targets. For example, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) is a monthly study conducted by Statistics Canada, who define the target population as “all members of the selected household who are 15 years old and older, whether they work or not.” Asking every Canadian meeting this definition would be costly and the process would be long: the characteristic of interest (employment) is also a snapshot in time and can vary when the person leaves a job, enters the job market or become unemployed. In this example, collecting a census would be impossible and too costly.

In general, we therefore consider only samples to gather the information we seek to obtain. The purpose of statistical inference is to draw conclusions about the population, but using only a share of the latter and accounting for sources of variability. The pollster George Gallup made this great analogy between sample and population:

One spoonful can reflect the taste of the whole pot, if the soup is well-stirred

A sample is a sub-group of individuals drawn at random from the population. We won’t focus on data collection, but keep in mind the following information: for a sample to be good, it must be representative of the population under study.

The Parcours AGIR at HEC Montréal is a pilot project for Bachelor in Administration students that was initiated to study the impact of flipped classroom and active learning on performance.

Do you think we can draw conclusions about the efficacy of this teaching method by comparing the results of the students with those of the rest of the bachelor program? List potential issues with this approach addressing the internal and external validity, generalizability, effect of lurking variables, etc.

Because the individuals are selected at random to be part of the sample, the measurement of the characteristic of interest will also be random and change from one sample to the next. While larger samples typically carry more information, sample size is not a guarantee of quality, as the following example demonstrates.

Example 1.4 (Polling for the 1936 USA Presidential Election) The Literary Digest surveyed 10 millions people by mail to know voting preferences for the 1936 USA Presidential Election. A sizeable share, 2.4 millions answered, giving Alf Landon (57%) over incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt (43%). The latter nevertheless won in a landslide election with 62% of votes cast, a 19% forecast error. Biased sampling and differential non-response are mostly responsible for the error: the sampling frame was built using ``phone number directories, drivers’ registrations, club memberships, etc.’’, all of which skewed the sample towards rich upper class white people more susceptible to vote for the GOP.

In contrast, Gallup correctly predicted the outcome by polling (only) 50K inhabitants. Read the full story here.

What are the considerations that could guide you in determining the population of interest for your study?

1.3.3 Sampling

Because sampling is costly, we can only collect limited information about the variable of interest, drawing from the population through a sampling frame (phone books, population register, etc.) Good sampling frames can be purchased from sampling firms.

In general, randomization is necessary in order to obtain a representative sample5, one that match the characteristics of the population. Failing to randomize leads to introduction of bias and generally the conclusions drawn from a study won’t be generalizable.

Even when measurement units are selected at random to participate, there may be bias introduced due to non-response. In the 1950s, conducting surveys was relatively easier because most people were listed in telephone books; nowadays, sampling firms rely on a mix of interactive voice response and live callers, with sampling frames mixing landlines, cellphones and online panels together with (heavy) weighting to correct for non-response. Sampling is a difficult problem with which we engage only cursorily, but readers are urged to exercise scrutiny when reading papers.

Reflect on the choice of platform used to collect answers and think about how it could influence the composition of the sample returned or affect non-response in a systematic way.

Before examining problems related to sampling, we review the main random sampling methods. The simplest is simple random sampling, whereby \(n\) units are drawn completely at random (uniformly) from the \(N\) elements of the sampling frame. The second most common scheme is stratified sampling, whereby a certain numbers of units are drawn uniformly from strata, namely subgroups (e.g., gender). Finally, cluster sampling consists in sampling only from some of these subgroups.

Example 1.5 (Sampling schemes in a picture) Suppose we wish to look at student satisfaction regarding the material taught in an introductory statistics course offered to multiple sections. The population consists of all students enrolled in the course in a given semester and this list provides the sampling frame. We can define strata to consist of class group. A simple random sample would be obtaining by sampling randomly abstracting from class groups, a stratified sample by drawing randomly a number from each class group and a cluster sampling by drawing all students from selected class groups. Cluster sampling is mostly useful if all groups are similar and if the costs associated to sampling from multiple strata are expensive.

Figure 1.4 shows three sampling schemes: the middle corresponds to stratum (e.g., age bands) whereas the right contains clusters (e.g., villages or classrooms).

Stratified sampling is typically superior if we care about having similar proportions of sampled in each group and is useful for reweighting: in Figure 1.4, the true proportion of sampled is \(1/3\), with the simple random sampling having a range of [\(0.22, 0.39\)] among the strata, compared to [\(0.31, 0.33\)] for the stratified sample.

The credibility of a study relies in large part on the quality of the data collection. Why is it customary to report descriptive statistics of the sample and a description of the population?

There are other instances of sampling, most of which are non-random and to be avoided whenever possible. These include convenience samples, consisting of measurement units that are easy to access or include (e.g., friends, students from a university, passerby in the street). Much like for anecdotal reports, these measurement units need not be representative of the whole population and it is very difficult to understand how they relate to the latter.

In recent years, there has been a proliferation of studies employing data obtained from web experimentation plateforms such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), to the point that the Journal of Management commissioned a review (Aguinis, Villamor, and Ramani 2021). These samples are subject to self-selection bias and articles using them should be read with a healthy dose of skepticism. Unless good manipulation checks are conducted (e.g., to ensure participants are faithful and answer in a reasonable amount of time), I would reserve these tools for paired samples (e.g., asking people to perform multiple tasks presented in random order) for which the composition of the population is less important. To make sure your sample matches the target population, you can use statistical tests and informal comparison and compare the distribution of individuals with the composition obtained from the census.

1.4 Examples of experimental designs

The field of experimental design has a long history, starting with agricultural field trials.

Example 1.6 (Agricultural field trials at the Rothamsted Research Station.) The Rothamsted Research Station in the UK has been conducting experiments since 1843. Ronald A. Fisher, who worked 14 years at Rothamsted from 1919, developed much of the statistical theory underlying experimental design, inspired from his work there. Yates (1964) provides a recollection of his contribution to the field.

Experimental design revolves in large part in understanding how best to allocate our resources, determine the impact of policies or choosing the most effective “treatment” from a series of option.

Example 1.7 (Modern experiments and A/B testing) Most modern experiments happen online, with tech companies running thousands of experiments on an ongoing basis in order to discover improvement to their interfaces that lead to increased profits. An Harvard Business Review article (Kohavi and Thomke 2017) details how small tweaks to the display of advertisements in the Microsoft Bing search engine landing page lead to a whooping 12% increase in revenues. Such randomized control trials, termed A/B experiments, involve splitting incoming traffic into separate groups; each group will see different views of the webpage that differ only ever slightly. The experimenters then compare traffic and click revenues. At large scale, even small effects can have major financial consequences and can be learned despite the large variability in customer behaviour.

There are also multiple examples of randomized control experiments used for policy making.

Example 1.8 (Experiments on wellness programs) Song and Baicker (2019) conducted a large randomized trial over a period of 18 months to study the impact of wellness programs in US companies. The industry, worth more than 8 billions USD, has significantly increased following the passage of the Affordable Care Act, aka Obamacare. The findings are vulgarized in a press release by Jake Miller from Harvard News & Research: they show that, while there was seemingly an impact on physical activity and well-being, there were no evidence of changes in absenteeism, job tenure and job performance. Jones, Molitor, and Reif (2019) reach similar conclusion.

These findings are strikingly different from previous observational studies, which found increase participation in sportive activities, increased job duration, reduced medical spendings.

Example 1.9 (STAR) The Tennessee’s Student Teacher Achievement Ratio (STAR) project (Achilles et al. 2008) is another important example of large scale experiment with broad ramifications. The study suggested that smaller class sizes lead to better outcomes of pupils.

Over 7,000 students in 79 schools were randomly assigned into one of 3 interventions: small class (13 to 17 students per teacher), regular class (22 to 25 students per teacher), and regular-with-aide class (22 to 25 students with a full-time teacher’s aide). Classroom teachers were also randomly assigned to the classes they would teach. The interventions were initiated as the students entered school in kindergarten and continued through third grade.

Example 1.10 (RAND health care programs) In a large-scale multiyear experiment conducted by the RAND Corporation (Brook et al. 2006), participants who paid for a share of their health care used fewer health services than a comparison group given free care. The study concluded that cost sharing reduced “inappropriate or unnecessary” medical care (overutilization), but also reduced “appropriate or needed” medical care.

The HIE was a large-scale, randomized experiment conducted between 1971 and 1982. For the study, RAND recruited 2,750 families encompassing more than 7,700 individuals, all of whom were under the age of 65. They were chosen from six sites across the United States to provide a regional and urban/rural balance. Participants were randomly assigned to one of five types of health insurance plans created specifically for the experiment. There were four basic types of fee-for-service plans: One type offered free care; the other three types involved varying levels of cost sharing — 25 percent, 50 percent, or 95 percent coinsurance (the percentage of medical charges that the consumer must pay). The fifth type of health insurance plan was a nonprofit, HMO-style group cooperative. Those assigned to the HMO received their care free of charge. For poorer families in plans that involved cost sharing, the amount of cost sharing was income-adjusted to one of three levels: 5, 10, or 15 percent of income. Out-of-pocket spending was capped at these percentages of income or at $1,000 annually (roughly $3,000 annually if adjusted from 1977 to 2005 levels), whichever was lower.

Families participated in the experiment for 3–5 years. The upper age limit for adults at the time of enrollment was 61, so that no participants would become eligible for Medicare before the experiment ended. To assess participant service use, costs, and quality of care, RAND served as the families’ insurer and processed their claims. To assess participant health, RAND administered surveys at the beginning and end of the experiment and also conducted comprehensive physical exams. Sixty percent of participants were randomly chosen to receive exams at the beginning of the study, and all received physicals at the end. The random use of physicals at the beginning was intended to control for possible health effects that might be stimulated by the physical exam alone, independent of further participation in the experiment.

There are many other great examples in the dedicated section of Chapter 10 of Telling stories with data by Rohan Alexander (Alexander 2022). Section 1.4 of Berger, Maurer, and Celli (2018) also lists various applications of experimental designs in a variety of fields.

1.5 Requirements for good experiments

Section 1.2 of Cox (1958) describes the various requirements that are necessary for experiments to be useful. These are

- absence of systematic error

- precision

- range of validity

- simplicity

We review each in turn.

1.5.1 Absence of systematic error

This point requires careful planning and listing potential confounding variables that could affect the response.

Example 1.11 (Systematic example) Suppose we wish to consider the differences in student performance between two instructors. If the first teaches only morning classes, while the second only teaches in the evening, it will be impossible to disentangle the effect of timing with that of instructor performance. Such comparisons should only be undertaken if there is compelling prior evidence that timing does not impact the outcome of interest.

The first point raised by Cox is thus that we

ensure that experimental units receiving one treatment differ in no systematic way from those receiving another treatment.

This point also motivates use of double-blind procedures (where both experimenters and participants are unaware of the treatment allocation) and use of placebo in control groups (to avoid psychological effects, etc. associated with receiving treatment or lack thereof).

Randomization6 is at the core of achieving this goal, and ensuring measurements are independent of one another also comes out as corollary.

1.5.2 Variability

The second point listed by Cox (1958) is that of the variability of estimator. Much of the precision can be captured by the signal-to-noise ratio, in which the difference in mean treatment is divided by its standard error, a form of effect size. The intuition should be that it’s easier to detect something when the signal is large and the background noise is low. The latter is a function of

- the accuracy of the experimental work and measurements apparatus and the intrinsic variability of the phenomenon under study,

- the number of experimental and measurement units (the sample size).

- the choice of design and statistical procedures.

Point (a) typically cannot be influenced by the experimenter outside of choosing the response variable to obtain more reliable measurements. Point (c) related to the method of analysis, is usually standard unless there are robustness considerations. Point (b) is at the core of the planning, notably in choosing the number of units to use and the allocation of treatment to the different (sub)-units.

1.5.3 Generalizability

Most studies are done with an objective of generalizing the findings beyond the particular units analyzed. The range of validity thus crucially depends with the choice of population from which a sample is drawn and the particular sampling scheme. Non-random sampling severely limits the extrapolation of the results to more general settings. This leads Cox to advocate having

not just empirical knowledge about what the treatment differences are, but also some understanding of the reasons for the differences.

Even if we believe a factor to have no effect, it may be wise to introduce it in the experiment to check this assumption: if it is not a source of variability, it shouldn’t impact the findings and at the same time would provide some more robustness.

If we look at a continuous treatment, than it is probably only safe to draw conclusions within the range of doses administered. Comic in Figure 2.3 is absurd, but makes this point.

Example 1.12 (Generalizability) Replication studies done in university often draw participants from students enrolled in the institutions. The findings are thus not necessarily robust if extrapolated to the whole population if there are characteristics for which they have strong (familiarity to technology, acquaintance with administrative system, political views, etc). These samples are often convenience samples.

Example 1.13 (Spratt-Archer barley in Ireland) Example 1.9 in Cox (1958) mentions recollections of “Student”7 on Spratt-Archer barley, a new variety of barley that performed well in experiments and whose culture the Irish Department of Agriculture encouraged. Fuelled by a district skepticism with the new variety, the Department ran an experiment comparing the yield of the Spratt-Archer barley with that of the native race. Their findings surprised the experimenters: the native barley grew more quickly and was more resistant to weeds, leading to higher yields. It was concluded that the initial experiments were misleading because Spratt-Archer barley had been experimented in well-farmed areas, exempt of nuisance.

1.5.4 Simplicity

The fourth requirement is one of simplicity of design, which almost invariably leads to simplicity of the statistical analysis. Randomized control-trials are often viewed as the golden rule for determining efficacy of policies or treatments because the set of assumptions they make is pretty minimalist due to randomization. Most researchers in management are not necessarily comfortable with advanced statistical techniques and this also minimizes the burden. Figure 1.7 shows an hypothetical graph on the efficacy of the Moderna MRNA vaccine for Covid: if the difference is clearly visible in a suitable experimental setting, then conclusions are easily drawn.

Randomization justifies the use of the statistical tools we will use under very weak assumptions, if units measurements are independent from one another. Drawing conclusions from observational studies, in contrast to experimental designs, requires making often unrealistic or unverifiable assumptions and the choice of techniques required to handle the lack of randomness is often beyond the toolbox of applied researchers.

- Define the following terms in your own word: experimental unit, factor, treatment.

- What is the main benefit of experimental studies over observational studies?

The preceding paragraph shouldn’t be taken to mean that one cannot get meaningful conclusions from observational studies. Rather, I wish to highlight that controlling for the non-random allocation and potential confounding is a much more complicated task, requires practitioners to make stronger (and sometimes unverifiable) assumptions and requires using a different toolbox (including, but not limited to differences in differences, propensity score weighting, instrumental variables). The book The Effect: An Introduction to Research Design and Causality by Nick Huntington-Klein gives a gentle nontechnical introduction to some of these methods.↩︎

Since continuous data can take any value in the interval, we can’t talk about the probability of a specific value. Rather, the density curve encodes the probability for any given area: the higher the curve, the more likely the outcome.↩︎

The parameters of most commonly used theoretical distributions do not directly relate to the mean and the variance, unlike the normal distribution.↩︎

A factor is a categorical variable, thus the experimental factor encodes the different groups to compare↩︎

Note this randomization is different from the one in assigning treatments to experimental units!↩︎

The percentage of participants need not be equiprobable, nor do we need to assign the same probability to each participant. However, going away from equal number of people per group has consequences and makes the statistical analysis more complicated.↩︎

William Sealy Gosset↩︎